‘Can you spell lynching?’: lawyer’s shocking note in Texas execution case | Texas

In April 1999, John Balentine, a Black man on trial for murder in Amarillo, Texas, sat before an all-white jury as they deliberated whether he should live or die.

Should he be given a life sentence, in which case he would probably end his days behind prison bars? Or should they send him to death row to await execution?

Balentine had been convicted days earlier of murdering three white teenagers who had threatened to kill him because he was romantically engaged with one of the teenagers’ white sisters – an interracial liaison widely frowned upon in heavily segregated Amarillo. Now it was the sentencing phase of the trial, when his fate would be decided.

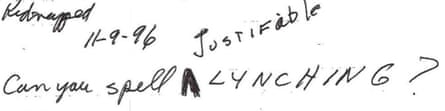

As the trial ground towards its climax, a pair of Balentine’s defense lawyers shuffled a note between themselves. “Can you spell LYNCHING?” one of them quipped in his crabby handwriting.

Before handing the note back, the second lawyer inserted a word: “Can you spell Justifiable LYNCHING?”

A facsimile of the exchange is contained among 223 pages of evidence submitted to the Texas court of criminal appeals this week as part of a last-ditch attempt to save Balentine’s life. The prisoner was scheduled to be executed by lethal injection next Wednesday, and although a local court this week ordered the death warrant to be recalled on procedural grounds, the state is pressing for the judicial killing to go ahead.

Accompanying the new evidence package, Balentine’s current legal team has filed a petition which outlines the many disturbing anomalies behind his death sentence. The “justifiable lynching” note written by his own defense lawyers – which the petition decries as “unconscionable” and “stunning in disgust for their client” – is just one example of the racial toxicity that the lawyers argued permeated the proceedings.

The petition does not argue that Balentine is innocent. Nor does it challenge the facts of his conviction: that on January 21, 1998, he broke into the Amarillo house of Mark Caylor, 17, Kai Brooke Geyer, 15, and Steven Watson, 15, and shot them to death with a 32-caliber pistol as they lay sleeping.

“This is not a whodunit,” said Shawn Nolan, the lead counsel appealing to Balentine’s pending execution. “But this is a standout case. We often see some racial animus creeping into the system, but in this case it is so overt, it is really striking.”

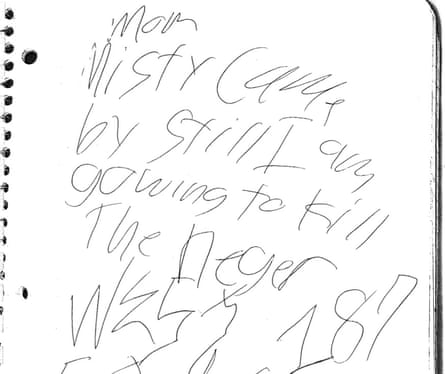

Racial conflict was present at the start of the grim sequence of events that has now brought Balentine, 54, to the edge of the death chamber. The trigger was his relationship with Misty Caylor, a white woman, which resulted in the racist wrath of her brother Mark.

The 17-year-old had a violent past. He had recently been released from a juvenile boot camp after firing bullets at a house. Incensed by his sister’s association with a Black man, he acquired another firearm and told several acquaintances that he planned to use it.

Detectives found a note at the crime scene in which Caylor had written: “I am gowing [sic] to kill the country”. He added the number 187 – hip-hop slang for “murder” based on section 187 of the California penal code.

Another brother, Chris Caylor, testified that shortly before the shootings he pinned a piece of paper referencing the Ku Klux Klan to Balentine’s front door.

“This case was racially motivated from the beginning,” Nolan said. “These people were coming after John because of the interracial relationship, and his defense lawyers at trial really dropped the ball on presenting that evidence to the jury.”

Balentine confessed to the murders soon after he was arrested, and the Texas criminal justice machine cranked into gear. Here again, issues of race and racial bias were present from the start.

The trial prosecutor removed from the pool of potential judges the only two African Americans available – creating an exclusively white jury. When it was put to the prosecutor that the strikes were discriminatory – and thus unlawful under the US constitution – he countered that he had based his decision on an innocent question.

He asked prospective jurors: did they have any doubts that OJ Simpson had been guilty of the 1994 murders of his wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend (Simpson was acquitted, though later found responsible in a civil trial)?

Both Black individuals said that, yes, they did have doubts about Simpson’s guilt, and were thus removed from the jury pool. Yet the prosecutor did not explain why he chose not to strike other potential judges who were white and who expressed exactly the same reservations.

When Nolan began digging into the case as Balentine’s appeal lawyer a few years ago, he was dismayed to discover a wealth of mitigating evidence that had never been put before the jury. In his opinion, such evidence would not have condoned the triple murders but might have placed Balentine’s homicidal behavior in context.

“We found compelling evidence of unbelievable poverty in John’s childhood, horrific physical and sexual abuse as a child, evidence that he suffered from long-term brain damage – none of it was presented to the jury because his defense lawyers did such a terrible job. That’s why John ended up on death row.”

Nolan’s claim is supported by some of the judges. Steve Fulton said in a deposition in September 2021 that “I didn’t know Balentine was molested or beaten or any of that. If I had known, I would not have voted to give him a death sentence.”

Another judge, Tara Smith, who was deposited in June 2021, said she was saddened to learn years after the event that they had been unaware of critical information about Balentine’s past. “It seems unfair not to have heard things about John, like the sexual abuse he suffered, or racism in his childhood, or brain damage that causes poor decision-making.”

A large swath of the petition is reserved for discussion of Dory England, the jury’s foreperson. The account bears comparison to Twelve Angry Men, the 1957 film that revolves around the deliberations of a jury at a murder trial – except in reverse.

Like Juror Eight, the character played by Henry Fonda in Sidney Lumet’s celebrated film, England managed to sway the votes of several of his fellow judges. Unlike Juror Eight, however, he used his formidable powers of persuasion not to spare the defendant, but to send him to death row.

According to the testimony of fellow judges, England succeeded in cajoling at least four of the 12 to change their vote from a life sentence to the death penalty. The petition bluntly states that “the jury foreman was a racist, who believed that it was up to him to make sure that Mr Balentine would be killed, and, to that end, bullied jurors who thought a life sentence was appropriate into changing their minds ”.

From a young age growing up in Amarillo, England harbored racist tendencies, the petition suggests. Among the packages of evidence presented to the Texas appeals court was the deposited testimony of Lola Perkins, who looked after England as his guardian when he was a young teenager.

Perkins recalled a fight that England was instigated at school in the early 1970s, at a time when his Amarillo middle school was being desegregated. She said: “Dory started the fight because he did not like Black people, the ones he called [the N-word]. He was a racist against Black people because that is how he was raised. It’s how a lot of us were raised in Amarillo, back when Blacks and whites did not mesh.”

England went on to join the Marine Corps. In a legal declaration in May 2021, just three weeks before he died, he said that his combat experiences had informed his attitude as a foreperson at Balentine’s trial.

He had pushed for Balentine’s execution, he said, because he was convinced that if the prisoner were ever released from custody he would personally have to track Balentine down and kill him. “If I ever saw Balentine on the street, I’d shoot him myself,” he said.

England went on: “I knew if the others opted for life there was a chance he could get paroled, I would need to hunt him down. I’ve been in combat and I’ve come face to face with killers and I’ve killed more people than I can recall, so I understand what needs to happen to keep people safe.”

Such a violent fantasy of hunting Balentine and gunning him down not only bore echoes of the “justifiable lynching” note shuffled between the prisoner’s defense lawyers, it was also based on a fallacy. At the time of Balentine’s trial, the earliest the prisoner would have been eligible for parole on a life sentence was after 40 years, and even then his chances of being released were less than slim.

“Texas doesn’t parole people on murder cases, they just don’t,” Nolan said.

England described in his own words the extreme methods he used to browbeat fellow judges into changing their vote. He recalled how when the 12 women and men first entered the jury room and began their deliberations on the sentence, four of them opposed the death penalty.

“I am pretty stubborn and pretty aggressive. I don’t play well with others. I made it clear that we were chosen to take care of this problem, and that the death penalty was the only answer.”

He added: “I made it clear that what we were doing was biblically justified.”

England also recalled how he dealt with one of the female judges who was so disturbed by the possibility of Balentine being executed that she wrote a note saying that she did not want to impose the death penalty. When England discovered the note, he did not arrange for it to be passed to the judge as forepersons are supposed to do.

“I ripped it up and didn’t leave the room,” he said.

England’s fellow judge, Tara Smith, also noted in her deposition that there had been holdouts to a death penalty among the 12. “A couple of those folks may have felt like they couldn’t express that they didn’t want to sentence John to death. The foreman was a really strong personality,” she said.

England was himself aware of the impact his demeanor had on other jurors. After the sentence was handed down, the prosecutors came to talk to the 12 and asked them whether they felt they had been able to project their opinions inside the jury room.

“He wouldn’t let us!” a female juror uttered, pointing to the foreperson. England recounted that story in his own deposition, adding the wry remark: “I’m pretty tough in that way.”

With so much material pointing to the mishandling of Balentine’s sentencing phase at trial, and with so much evidence of racial animus in the case, Nolan is left reflecting on the state of the death penalty in Texas. Under constitutional law, racial discrimination is barred from the judicial process, while the ultimate punishment is supposed to be reserved only for the most heinous, cold-blooded crimes.

“This is not the worst of the worst,” Nolan said. “His life was threatened, there was so much mitigation that the jury never reached, and the racism is just so pervasive. A court needs to step in and put the brakes on this.”